“ Interestingly, the work that tried to please the least was the most compelling. Hayes Biggs’ piece Ave Formosissima harkens back to the dance-mad, melismatic and slightly raucous music of the Middle Ages. But the score, with its zig-zagging lines and pungent dissonances, is genuinely contemporary.”

—New York Times

“ A Consuming Fire, a short, zesty trio by Hayes Biggs, led off the evening. The piece is framed by some engagingly angular rhythmic writing, with a lyrical nougat at the center.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“ [The] most convincing and coherent performance [was] Hayes Biggs’ homage to his composer/pianist colleague Eric Moe, E.M. am Flügel, a short piece with romantic gestures and echoes of Berg and Stravinsky.”

—Aufbau

“ The Mass for All Saints would be an exciting challenge for those choirs skilled in precise intonation and rhythmic agility. Biggs writes with knowledge of and respect for the expressive capabilities of the human voice.”

—Choral Journal

“ Hayes Biggs’s wedding motet Tota Pulchra Es, here being sung for the first time, impressed by its quiet solemnity and neat working of its expressive opening motif: not empty fanfares but a reminder of the seriousness and privacy of love.”

—New York Times

“ Mass for All Saints by composer Hayes Biggs releases shadows transformed into tendrils of light by the arabesque of the vocal line. Contrapuntal procedures are used to their utmost expressive effect. [It] is a work of a melodist of talent in the manner of Puccini, or better yet, Respighi.”

—La Liberté

“ The Biggs song, Northeast Reservation Lines, is a real party piece... the sneakiness of the changes, the liveliness of the music and the verve of the performance worked handily... a potential recital hit in the vein of Bernstein’s I Hate Music cycle.”

—The Village Voice

“ All the works tried a return to tonality typical of the decade; the most successful made the return oblique and ambiguous. Hayes Biggs’ O Sacrum Convivium took off from the motet of Tallis, yet it handsomely reconfigured early modes in a modernistic scheme of free tonality.”

—New York Times

“ Hayes Biggs’ To Becalme His Fever... is a vivid evocation of anxiety, fits and repose. The language embraces pointillistic colors, romantic lines and prickly episodes when the demons hover. Biggs claims a forceful and subtle dramatic hand, along with a keen command of instrumental resources.”

—The Plain Dealer

Hayes Biggs, Composer

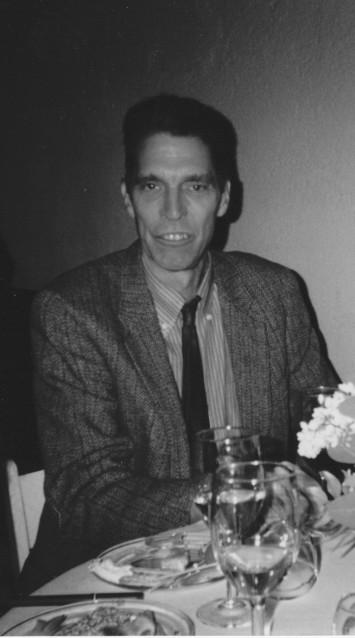

George Edwards (1943-2011)

Below is an excerpt from liner notes I wrote last year for an Albany Records CD, Music of George Edwards (TROY1264). Though I never formally studied composition with him, George had a significant impact on my development as a composer and teacher, and profoundly influenced my approach to listening to as well as thinking and writing about music. While the sheer force of his intelligence and vast knowledge of music and literature could be intimidating, and his wit at times biting, he also was one of the most fair-minded people I have ever met, and eminently capable of great kindness and generosity. His Collected Essays on Modern and Classical Music (Scarecrow Press, 2008) affords an excellent introduction to the brilliance of his analytic insights. George was a superb composer, producing music that seamlessly reconciles modernist rigor, contrapuntal mastery and an essentially late Romantic sensibility. Sadly, in his final years George suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease, which, over time, stripped away these capacities. His wife, the poet Rachel Hadas, has written a moving chronicle of those years, Strange Relation: A Memoir of Marriage, Dementia, and Poetry. (Paul Dry Books, 2011). Rachel also has posted on her website a lovely tribute to George by their son Jonathan, whose blog, Ill Wind, includes postings about his father, including explorations of George’s travel diaries and numerous photographs. All of these I commend to you, along with a remembrance from George’s friend and colleague, the composer Fred Lerdahl.

In the fall of 1982, George Edwards taught a seminar at Columbia University called “Twentieth Century Styles and Techniques.” I signed up for his class, having recently arrived in New York to begin my doctoral studies in composition at Columbia. Though I did not know George and had not yet heard a note of his music, it quickly became clear while sitting in that seminar room that I was in the presence of a formidable intellect. The first work we explored was a large portion of the third act of Tristan und Isolde, a score that—like all of the others we would examine that semester—he knew intimately, playing entire passages from memory on the piano to illustrate his points. His remarkable abilities as a musical analyst were immediately impressive; it was equally impressive to learn what sorts of things left him unimpressed: pretentiousness, jargon, cant, modishness, and the uncritical acceptance and parroting of conventional wisdom. Whenever he posed a question to the class about the work at hand he was fully prepared to remain silent for what could seem an eternity until someone ventured a response. Only when it became obvious that an adequate one would not be forthcoming did he move to the blackboard and proceed to astonish us with the clarity, depth and precision of his thinking. George’s observations always were brilliant, but most importantly, they always were grounded not merely in what was visible in the pages of a score but also in what was genuinely hearable in the music.

The thoughtfulness and rigor that he brought to his teaching are equally evident in the essays that he wrote during the late 1980s and 1990s. Many of these originally appeared in various musical and literary journals. They have been gathered together (along with a few previously unpublished items) as Collected Essays on Modern and Classical Music, issued by Scarecrow Press in honor of Edwards’ retirement from Columbia University as MacDowell Professor of Music Emeritus. The essays, aimed at a sophisticated, musically cultured yet nonspecialist audience, reveal Edwards as a stylist of uncommon elegance, wit and insight as they treat a variety of subjects with which he has long been deeply engaged. These include the state of contemporary composition, postmodernist aesthetics and theory, the relationship between current notions of historically informed performance practice and musical modernism, and the analysis of music by Haydn and Schubert.

Many of the concerns reflected in Edwards’ work as a teacher and essayist are of a piece with those at the core of his compositional activity. Chief among these is his desire to create music that moves meaningfully through time. One of his persistent criticisms of modernist music is what he sees as its tendency to negate the sense of the passage of time and goal-directed motion in favor of an overemphasis on stasis, discontinuity and a sense of the musical work more as an object in space than as a powerful conveyor of a narrative. A pervasive awareness of musical time—including precise control of meter, phrasing and tempo relationships—is at the heart of Edwards’ attempt to wed quintessentially modernist gestures (including moments of stasis and discontinuity) with the temporal richness of the greatest music of the Western tradition.

His longtime friend and colleague, the composer and theorist Fred Lerdahl, identifies three basic strands in George’s music. First, he aptly describes it as “relentlessly contrapuntal,” citing J. S. Bach as a primary influence. Second, he notes that while Edwards’ music is not truly serial in its organization, the twelve-tone works of Schoenberg and Webern have had a profound effect on him as a composer. Besides their approach to pitch relationships, their influence on Edwards can be felt in his penchant for large melodic leaps, fragmented surfaces, and formal complexity and compression. In his essay ‘The Pleasure of Its Being Over’: A View of Contemporary Music, Edwards describes Schoenberg’s twelve-tone works as “among the most courageous and successful attempts to write modernist music which is also firmly attached to tradition.” Finally, Edwards has always had a strong affinity for the lyrical intensity and harmonic richness of late Romantic Austro-German repertoire, from Wagner through Mahler and the early tonal works of Schoenberg and Berg. These three strands, disparate as they might at first appear, coalesce in important ways to form the essence of George’s unique compositional voice. The Bachian polyphonic rigor undergirds, grounds and mitigates the modernist disjunction of the individual melodic lines. It is also worth noting that, despite the frequency of leaps in his melodies, there is always a significant amount of purely stepwise chromatic voice leading in Edwards’ linear writing, a condition that also obtains in much of the late Romantic music he so admires. The Schoenbergian/Webernian pitch manipulations, as often as not, are used to generate harmonies that would not be at all out of place in post-Wagnerian contexts.

With the publication of his essays and the release of this superb new recording, we are all fortunate to have the opportunity to engage with a composer and thinker of the first magnitude. At the end of the essay quoted above, having enumerated and discussed the difficulties attendant upon the reception by audiences and critics of challenging contemporary music, George manages to hold out some hope for its survival, as he muses with characteristic equanimity:

I have heard strong neoromantic works; and minimalism seems to compensate for the glacial pacing of the individual work by the rapidity with which it is recapitulating the history of music. No one can yet judge the possibilities for various hybrid musics. There will probably always be a few oddballs who take music seriously; they will be the only audience that matters. In any case, like those 17th-century soldiers who continued to wear armor long after battle was dominated by guns, I expect to continue writing romantic works in my own dialect of modernism.

3 Comments | Posted in Composers, George Edwards, News

Featured Audio —

© Hayes Biggs | Site by Roundhex

Comments

I had intended that this post go up much earlier, in October, but logistics and a hurricane/”superstorm” intervened!

Hayes, this is a beautiful tribute to someone I always respected and admired from a certain distance. It was a pleasure to read it and to remember what a presence George really was. Thanks for that!

Wade, thanks for this; I remember that you sat in that seminar along with me and many others. It’s good to hear from you. All the best of the season to you!

Leave a Comment