“ Interestingly, the work that tried to please the least was the most compelling. Hayes Biggs’ piece Ave Formosissima harkens back to the dance-mad, melismatic and slightly raucous music of the Middle Ages. But the score, with its zig-zagging lines and pungent dissonances, is genuinely contemporary.”

—New York Times

“ A Consuming Fire, a short, zesty trio by Hayes Biggs, led off the evening. The piece is framed by some engagingly angular rhythmic writing, with a lyrical nougat at the center.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“ [The] most convincing and coherent performance [was] Hayes Biggs’ homage to his composer/pianist colleague Eric Moe, E.M. am Flügel, a short piece with romantic gestures and echoes of Berg and Stravinsky.”

—Aufbau

“ The Mass for All Saints would be an exciting challenge for those choirs skilled in precise intonation and rhythmic agility. Biggs writes with knowledge of and respect for the expressive capabilities of the human voice.”

—Choral Journal

“ Hayes Biggs’s wedding motet Tota Pulchra Es, here being sung for the first time, impressed by its quiet solemnity and neat working of its expressive opening motif: not empty fanfares but a reminder of the seriousness and privacy of love.”

—New York Times

“ Mass for All Saints by composer Hayes Biggs releases shadows transformed into tendrils of light by the arabesque of the vocal line. Contrapuntal procedures are used to their utmost expressive effect. [It] is a work of a melodist of talent in the manner of Puccini, or better yet, Respighi.”

—La Liberté

“ The Biggs song, Northeast Reservation Lines, is a real party piece... the sneakiness of the changes, the liveliness of the music and the verve of the performance worked handily... a potential recital hit in the vein of Bernstein’s I Hate Music cycle.”

—The Village Voice

“ All the works tried a return to tonality typical of the decade; the most successful made the return oblique and ambiguous. Hayes Biggs’ O Sacrum Convivium took off from the motet of Tallis, yet it handsomely reconfigured early modes in a modernistic scheme of free tonality.”

—New York Times

“ Hayes Biggs’ To Becalme His Fever... is a vivid evocation of anxiety, fits and repose. The language embraces pointillistic colors, romantic lines and prickly episodes when the demons hover. Biggs claims a forceful and subtle dramatic hand, along with a keen command of instrumental resources.”

—The Plain Dealer

Hayes Biggs, Composer

Walter Hilse plays my Hymn Tune Preludes, Saturday, October 24, 2015

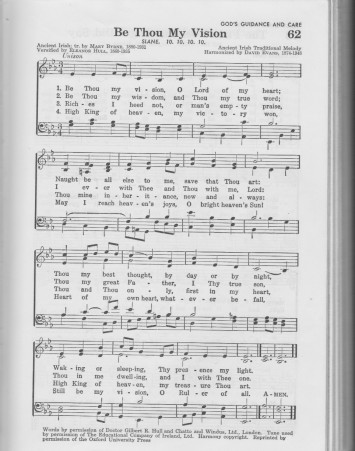

This coming Saturday, October 24, at 3:00 PM, the second and third of my Three Hymn Tune Preludes (2010) will be heard on the Bach at St. Peter’s series at St. Peter’s Church, Lexington Avenue at East 54th Street, performed by Walter Hilse, a wonderful organist, composer, teacher and all-around extraordinary musician. He will perform “Be Thou My Vision” (on the hymn tune Slane) and “Eternal Father, Strong to Save” (on John Bacchus Dykes’s Melita), alongside works of J. S. Bach, as well as another hymn-inspired work, “Just As I Am” from William Bolcom’s Gospel Preludes. Not only is Walter a master performer, he also brings a composer’s ear and sensibility to these pieces, and he will, I am confident, do a superb job with them. I hope any of you who happen to be in the New York City area that weekend will consider coming to this recital. A program note for all three of my pieces, including the first one, “He Leadeth Me! O Blessed Tho’t!” (tune: He Leadeth Me, by William Bradbury), follows below.

Several years ago I was given the opportunity to write my first major work for the organ, Three Hymn Tune Preludes (2010), through a commission from one of today’s foremost concert organists, Gail Archer. The commission, as well as my experience of her formidable performances of old and new organ repertoire, inspired me to be rather ambitious in the scope of this piece. Not only was it the first time I had written in a truly soloistic manner for the instrument, it also was a chance to engage with some of the first music I got to know well, the hymns that were sung week in, week out at the church in my hometown that my family attended.

Hymn singing was an important part of my life when I was growing up. We were members of First Baptist Church in Helena, Arkansas, where congregational participation in the hymns tended to be quite robust. One of my first and most crucial epiphanies as a musician — in fact, it probably is the single most important one — was the discovery, while a child sitting in church with my parents and sister, that I needn’t feel confined to singing the melody during the hymns, but could alternate at will among the four parts, and even switch to a different part mid-verse if so inclined. I could home in on the bass line as well as either of the middle parts as we were singing, and could comprehend the harmony, even if I was at that stage unable to use the correct terminology for describing it. Switching from part to part during the course of a hymn provided a much needed diversion during what, particularly for a child, could be rather lengthy and, yes, at times quite tedious services. I recall that my mother found this means of keeping myself entertained more than a little annoying, but I was not to be deterred. In any case I was exposed to many tunes — the great, the good, the bad, the ugly, and the dull (yes, I’m looking at you, “Blest Be the Tie”) — and that repertoire of hymns most certainly was a decisive factor in my musical development.

I’d had the idea to create a somewhat Bachian chorale prelude setting of William Bradbury’s “He Leadeth Me! O Blessed Tho’t!” many years ago, while an undergraduate, but never managed to get around to it. This probably was not a bad thing, as I more than likely would not have been in a position at that age to bring it confidently or competently to fruition. When my friend and colleague, the estimable Gail Archer commissioned me a few years ago to write a solo organ work for her, I immediately turned to that hymn first. I contacted Larry Earhart, who had been minister of music at First Baptist during my adolescent years. Larry kindly supplied me with a copy of the 1956 Baptist Hymnal — my old, worn copy that had originally belonged to my mother having been lost or misplaced — and I began working out my setting. It essentially unfolds in waves, beginning with a proclamatory introductory statement of the verse, followed by a transition at a softer yet still full dynamic. This passage introduces some of the harmonic and motivic material that will play a part in the main body of the piece, which is cast in a traditional chorale prelude texture, the tune set forth in long durations against a continuous and gently syncopated accompaniment. It is only in the concluding section that we at last hear the refrain of the hymn.

Slane, a tune best known to English-speaking congregations as “Be Thou My Vision,” comes from an old Irish ballad. My treatment of it has a rather cryptic introduction, followed by a full statement of the melody, presented as a cantus firmus in the pedal in a treble register. The tune is in long notes against what is mostly a gigue-like 6/8 meter. A return to the mood and texture of the beginning ensues, with an abrupt and enigmatic ending. This prelude is dedicated to the memory of David Ramsey, a wonderful organist and improviser who was my theory teacher at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, and who gave me my first lessons in how to write for the organ.

Melita, by John Bacchus Dykes, is usually sung to the words of Rev. William Whiting, who lived on the English coast, and had survived a terrible storm in the Mediterranean. Its pleading for divine protection for “those in peril on the sea,” led to its popularity in the United States as the Navy Hymn, and in The United Kingdom as the Royal Navy Hymn, a prayer for the brave servicemen and servicewomen who patrol the seas and protect those on shore. It has long been used to conclude services in the chapel of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. As I was composing this prelude at the MacDowell colony during the summer of 2010, the news constantly was filled with the horrors of the BP oil spill, and suddenly the meaning of the phrase “those in peril on the sea” expanded to those in peril living near or in the sea, including non-human mammals, birds, fish and other wildlife, as well as people who obtain their living from the sea. Another inspiration, no doubt, was Benjamin Britten’s powerful use of this melody in Noye’s Fludde, during the height of the storm sequence in that work, as Noah, his family, and all the animals are tossed about. My prelude starts with an austere fanfare constructed on motives from Dykes’s hymn that attempt with only partial success to coalesce into a statement of his melody. The tune is then heard complete in a canon between an upper voice on a manual and the bass in the pedal, with a free middle voice in tempestuous 16th notes between them on another manual. After this imitative section a final statement of the tune — in a chorale-like texture — is heard, beginning with a sense of anguish, ultimately leading to resignation and hope tinged with anxiety.

Gail Archer premiered all three of these preludes in New York City in January of 2012 at St. Paul’s Chapel at Columbia University.

Leave a Comment | Posted in News

Featured Audio —

© Hayes Biggs | Site by Roundhex

No Comments Yet

You can be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment