“ Interestingly, the work that tried to please the least was the most compelling. Hayes Biggs’ piece Ave Formosissima harkens back to the dance-mad, melismatic and slightly raucous music of the Middle Ages. But the score, with its zig-zagging lines and pungent dissonances, is genuinely contemporary.”

—New York Times

“ A Consuming Fire, a short, zesty trio by Hayes Biggs, led off the evening. The piece is framed by some engagingly angular rhythmic writing, with a lyrical nougat at the center.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“ [The] most convincing and coherent performance [was] Hayes Biggs’ homage to his composer/pianist colleague Eric Moe, E.M. am Flügel, a short piece with romantic gestures and echoes of Berg and Stravinsky.”

—Aufbau

“ The Mass for All Saints would be an exciting challenge for those choirs skilled in precise intonation and rhythmic agility. Biggs writes with knowledge of and respect for the expressive capabilities of the human voice.”

—Choral Journal

“ Hayes Biggs’s wedding motet Tota Pulchra Es, here being sung for the first time, impressed by its quiet solemnity and neat working of its expressive opening motif: not empty fanfares but a reminder of the seriousness and privacy of love.”

—New York Times

“ Mass for All Saints by composer Hayes Biggs releases shadows transformed into tendrils of light by the arabesque of the vocal line. Contrapuntal procedures are used to their utmost expressive effect. [It] is a work of a melodist of talent in the manner of Puccini, or better yet, Respighi.”

—La Liberté

“ The Biggs song, Northeast Reservation Lines, is a real party piece... the sneakiness of the changes, the liveliness of the music and the verve of the performance worked handily... a potential recital hit in the vein of Bernstein’s I Hate Music cycle.”

—The Village Voice

“ All the works tried a return to tonality typical of the decade; the most successful made the return oblique and ambiguous. Hayes Biggs’ O Sacrum Convivium took off from the motet of Tallis, yet it handsomely reconfigured early modes in a modernistic scheme of free tonality.”

—New York Times

“ Hayes Biggs’ To Becalme His Fever... is a vivid evocation of anxiety, fits and repose. The language embraces pointillistic colors, romantic lines and prickly episodes when the demons hover. Biggs claims a forceful and subtle dramatic hand, along with a keen command of instrumental resources.”

—The Plain Dealer

Hayes Biggs, Composer

More on George Edwards: Remarks Delivered at a Memorial Tribute

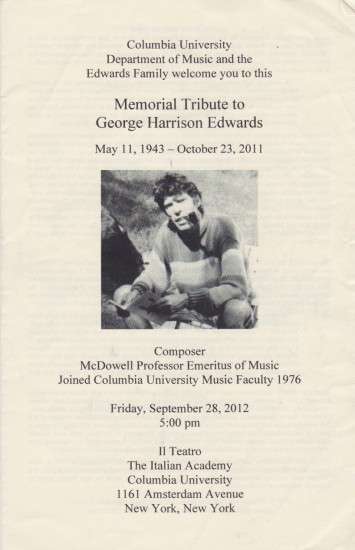

Last year I was asked by George’s wife, the poet Rachel Hadas, to participate in a memorial tribute for him. This took place on September 28, 2012 at Columbia University’s Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America. It was a lovely and often moving gathering, with Rachel, Jonathan (George and Rachel’s son), and many of George’s friends, colleagues and former students in attendance, and I was honored to have been invited, along with several distinguished speakers, including — among others — Columbia University musicologist Elaine Sisman and composers David Rakowski and Fred Lerdahl, to offer my reminiscences.

George’s tribute was a wonderful example of how such events can serve as occasions to celebrate and reflect upon the character and accomplishments of the person whose memory is being honored, while simultaneously avoiding the maudlin or morbid. To be sure, no attempt was made to sugarcoat the sad fact of George’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s Disease, which had been diagnosed in him at the age of sixty-one and from which he had suffered for a number of years. In fact, one of his physicians, Dr. James Noble, a Professor of Neurology at Columbia, also spoke at the memorial, sharing his recollections of meeting and working with George; he seemed particularly glad to make the acquaintance of and hear from those who had known George before the onset of his illness. For all this, though, there was not so much as a hint of sentimentality in any of the proceedings, something I’m certain the George we all knew would have been relieved to know. He was justly remembered as the brilliant composer, musical analyst, essayist and teacher he was, and as a generous colleague. He was praised as well for his steady, fair and even-handed leadership during his tenure as Chair of the Department of Music at Columbia. There also were stellar performances of George’s music: pianist Stephen Gosling gave a powerful account of the darkly brooding Suave Mari Magno (1984), and conductor Jeffrey Milarsky and a crackerjack ensemble consisting of flutist Tara O’Connor, clarinetist Alan Kay, violinist Aaron Boyd, cellist Jeremiah Campbell, percussionist Tom Kolor, and Mr. Gosling, brought to life the brilliant and pellucid textures of The Isle is Full of Noises (1995).

My little speech covers some of the same ground as my earlier post, taken primarily from liner notes written for the Albany Records CD of George’s music, but there are one or two other little tidbits that are new, as well as a bit more of a personal emphasis.

What made me especially happy about George’s memorial (and the reception that followed) was that there was a good amount of laughter — laughter engendered by anecdotes from several of the speakers (Elaine Sisman and Davy Rakowski particularly come to mind) that bespoke George’s quick wit and wicked sense of humor. To hear those stories was to hear George’s voice again, and for that I am and shall remain grateful.

Hayes Biggs: Remarks for George Edwards Memorial

Leave a Comment | Posted in Composers, George Edwards, News

Featured Audio —

© Hayes Biggs | Site by Roundhex

No Comments Yet

You can be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment